From Mass Propaganda Spectacle to Mass Political Protest: the Mediatic Spaces of Political Demonstrations

THE FOLLOWING CONFERENCE PRESENTATION REPRINTED HERE IS WITHOUT FOOTNOTES AND REFERENCES. ALL GRAPHICS ARE BY PTL, PLEASE CONTACT THE AUTHOR FOR REPRODUCTION RIGHTS. THIS ESSAY, GIVEN AT THE SSISCo CONFERENCE IN MODENA, IS IN PART EXCERPTED FROM MY PhD DISSERTATION, COMPLETED IN 2000: Masses in Motion: Spaces and Spectacle in Fascist Rome. 1919-1929. New York University Department of History.

My dissertation completed in 2000 focuses on the urban modernization of turn of the century Rome and the historically critical moment in the transformation of the mass spectacle. What emerges over the course of this period between 1921 and 1929 is a Fascist styled political spectacle that gradually shifted away from the familiar and traditional urban landscapes and moved to occupy the austere modern residential neighborhoods rising on the periphery of the Italian capital. In the process this history reveals that the oceanic rallies of the 1930s were neither so monolithic in character nor were they pure expressions of fervent religious secularism. Instead the very hesitant and unpremeditated manner in which these rituals found their place and form, points to a much more complex historic development shepherded not by the vision of Mussolini but by a cadre of astute party propagandists quick to turn to experiment.

Another unexpected twist in this particular history is performed by Italy’s war Veteran’s: this politically heterogeneous organization played a much more important role in resisting Fascist rule in the early years of Mussolini’s government than is usually credited them. The pawn of contention was the Tomb to the “Unknown Soldier,” that had been set into the colossal monument dedicated to King Vittorio Emanuele II in the heart of the ancient city. The Veterans resisted Fascist overtures that would have compromised the national monument’s unifying symbolism. The Fascist party was forced to find alternative sites to stage their political rituals, gradually leading to the development of a new style of spectacle fragmented into theme episodes and spread into the decentered landscapes on the margins of the capital.

In order to better understand how the public square is emerging as one of the most contested spheres of contemporary collective political expression in recent times, instigating the demarcation of new forms of political and mediatic space, its important to get an overview on the relationship between public spaces and mass movements.

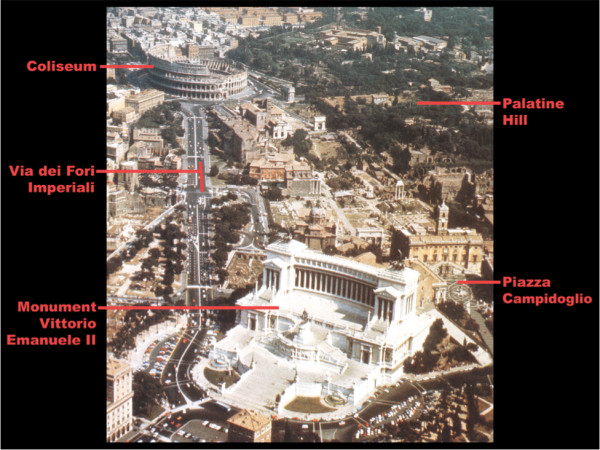

Today i will present —given the short amount of time—one of my case studies: the making of the Vittoriano, and the Monument to King Emanuele II’s emergent urban infrastructure. The complex history of this monument, its Risorgimento origins, its unexpected conversion into a memorial to a soldier and not the King, and its eventual exploitation by the Fascist State towards the end of the 1920s make this monument a perfect example of politicalised architecture. In my dissertation, i discussed how the Fascist Regime was pushed away from such symbolic centers, but as we will see shortly, this particular Monument can be seen as being transformed into a peripheral architecture, as its surrounding neighbourhoods were cleared away and transportation infrastructures introduced.

My thesis hinged on research into three primary components, that looked at pivotal moments concerning both pre-fascist and early fascist developments. the capital’s urban modernization and new infrastructure, the emergence of a new form of commemorative march as mass spectacle, and the integration of youth sports as a lynchpin to the making of these spectacles. Goebbels, as did also Leni Reifenstahl, could exploit Italy’s pioneering advances in the making of the political mass spectacle.

(see: Masses in Motion: Spaces and Spectacle in Fascist Rome, 1919-1929. 2000. Excerpts published in Victoria De Grazia, Sergio Luzzatto. Ed.s Il Fascismo. Un Dizionario Critico. Giulio Einaudi 2002).

The thesis examined and reconstructed the growing relationship between the invention of the modern propaganda spectacle, and the corollary urban transformation of Rome. The Fascist government’s expanding policies on the creation of monumental public mass spectacles culminated, by the late twenties, in a cinematic assembly of celebratory episodes.

However, the historical example I will present today, the development of the Vittoriano, both as an architectural monument and as a national symbol of Italian unity, provides a glimpse at a what can be considered to be a set of essential typologies that together shaped some of the most powerful national propaganda spectacles in the interwar period.

Mussolini’s vision of monumental Rome was ultimately more rhetorical than physical: his greatest contribution to the city’s development was to facilitate the progress of work already planned by his pre-fascist predecessors. Mussolini was satisfied to advance existing urban policies established around the turn of the century. These policies nonetheless proved critical to giving shape and style to the fascist movement, precisely because Rome’s gradual expansion and monumentalization provided the Fascists with an ample repertoire of celebratory architecture and urban spaces. As the Duce’s grip on power became more secure, he concentrated on redoubling these programs dedicated to the capital’s aggrandisement.

Rome’s development as a world capital was a haphazard process, initiated late in the Risorgimento period, with the city the last and most symbolic conquest in the drive for unification. Rome had been until then frozen in time, it hardly resembled the economic, political and industrial capital like its counterpart berlin—when it became the capital of unified Germany. Rome’s economy grew by market speculation, often not adhering to the simple urban masterplans that were introduced to structure the capital’s growth. Its been said the capital grew like a macchia d’olio == oil stain.

The largely unregulated pace of development inside the capital would have most likely continued along an indeterminate path if it were not for the advent of the competition to erect a national monument to Vittorio Emanuele II and the subsequent search to find a suitable site. the development of this monument introduced to the city a new potential urban center.

DEATH OF KING VITTORIO EMANUELE II

Following King Vittorio Emanuele II death in 1878, the Municipality of Rome decided to dedicate a commemorative monument to the King inside the capital. The project, in the increasingly caustic spirit of Unification, caught the imagination of the parliament, which took upon itself the study and execution of the project. The king in the meantime was buried in the Pantheon, as magnificently portrayed in the mural in the palazzo Comunale in Siena commemorating his burial ceremony.

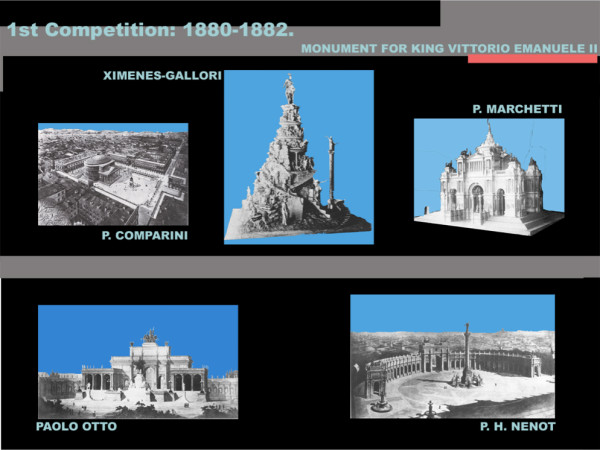

FIRST COMPETITION

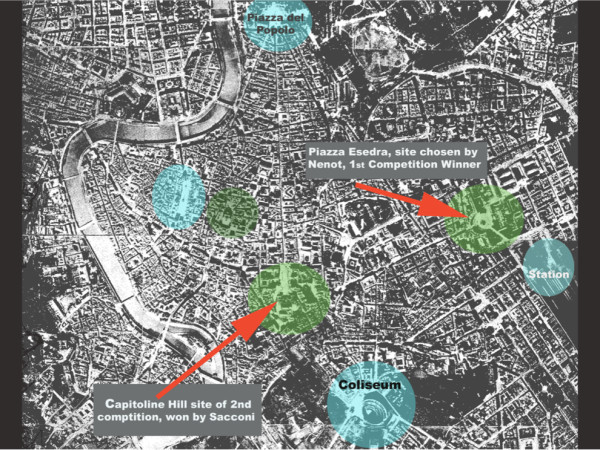

After much public debate, the commission settled for a competition format with no restrictions on foreign participants. Of 293 entrants competing in the first round reviewed in 1882, 40 were foreign submissions. 88 The first competition, published September 23, 1880 and concluded March 31,1882, was remarkable for setting so few formal constraints. Many of the competition entrants situated their design proposals in the newer districts around the Central Rail station, thus avoiding the heavy burden of working in the ancient center.

THE FIRST PRIZE WINNER NENOT

The award winning entry by the French architect P.H. Nenot, proposed for the site of the piazza Esedra, failed to garner sufficient public support, probably because the area was distant from the historical center. A political decision by the President of the Council Depretis on September 13, 1882 unconditionally established the northwest slope of the Capitoline Hill for the site of the monumental project.

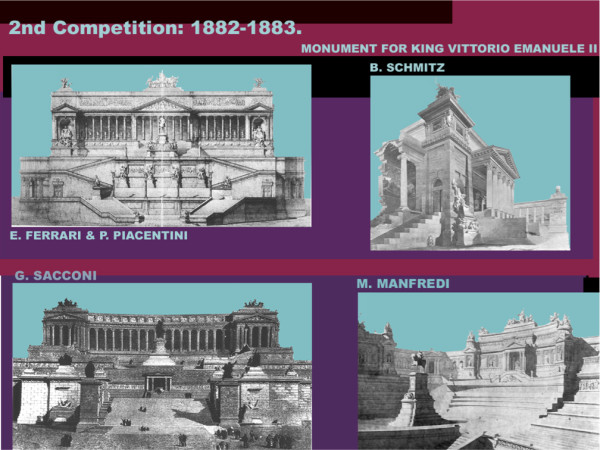

WINNING ARCHITECT SECOND COMPETITION

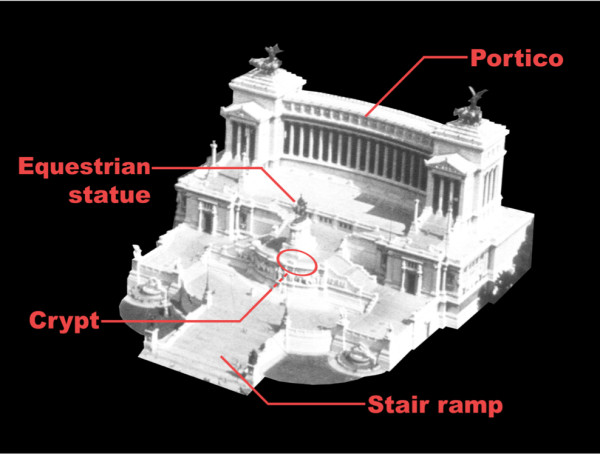

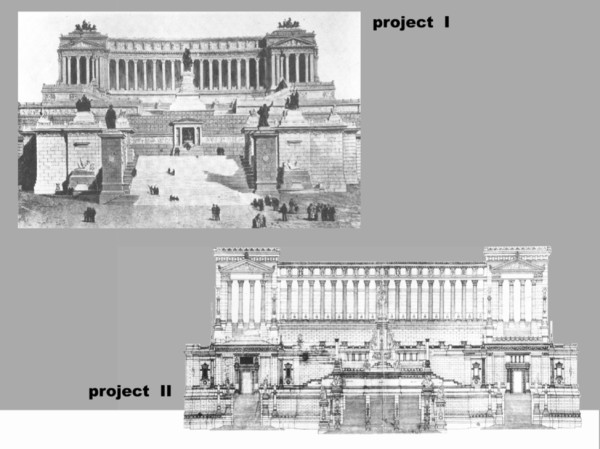

The winning design by Giuseppe Sacconi, awarded on June 26, 1884, borrowed generously from Beaux-Arts and Second Empire traditions. The composition may have been further inspired by archeological reconstruction underway in Germany around this time.

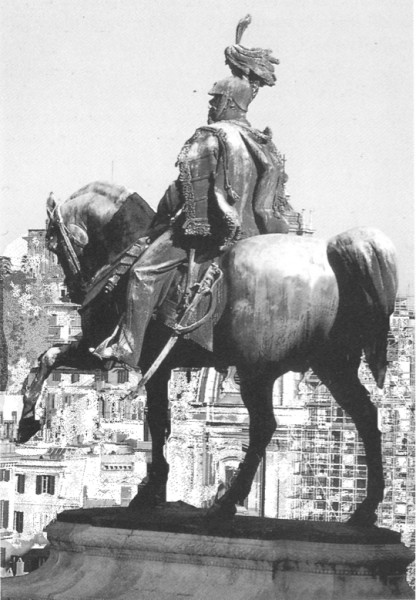

The hybrid scheme was organized into three parts: a broad access stair ramp, a mid terrace with the King’s equestrian statue, and projecting plinth surmounted by a horizontal portico. This last device featured an imperceptibly curved colonnade that was framed by flanking temple portals set in squat square towers. Each of these flanking portals supported a sculptural arrangement with a winged female figure leading a horse drawn chariot. The design for the Sacconi colonnade offered a neutral rhythmic backdrop to the King’s equestrian statue.

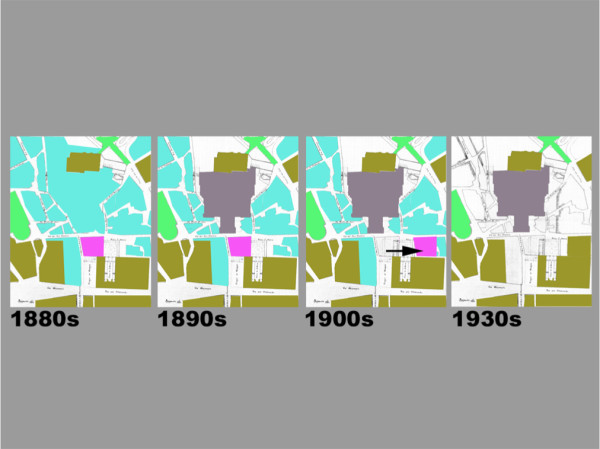

This edifying project would become, in the next thirty years, the most forceful mechanism in the historic center’s southern development. The monument and its eventual construction had a radical effect on the future course of the capital. The growing mountain of white Brescian marble forced a new pattern of development in this dense Medieval neighborhood. The gigantic scale of the monument demanded an ever-expansive foyer from which to view its rising bulk. The gradual razing of the urban fabric crowding around the monument made room for more than just an impressive urban square: the resulting piazza Venezia grew to become the contemporary nexus of the capital. The Fascists, as this history demonstrates, were not the only authors in this transformation. Mussolini’s entrance into the construction melee around the site came late, but succeeded in bringing what seemed to be a long and interminable building process to speedy resolution.

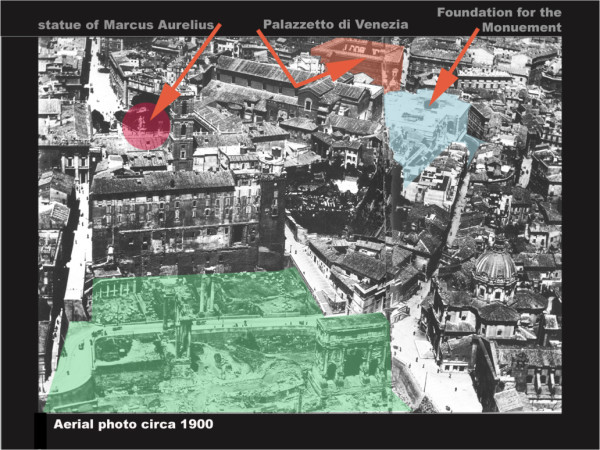

Palazzo Venezia before its was moved to make room for the central piazza.

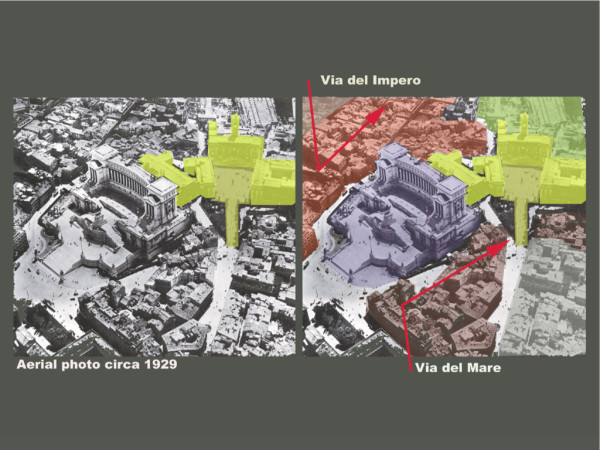

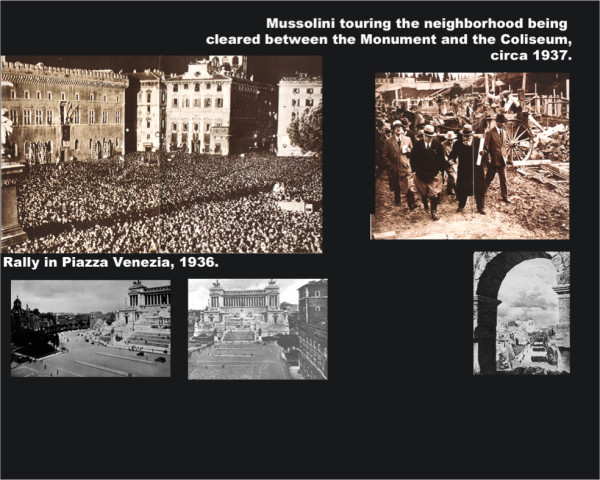

Aerial depicting the clearing of the two Medieval neighborhoods, making way for the creation of two new urban arteries. These avenues would allow for new transit lines to bring large numbers of people into Piazza Venezia, which by 1928 would begin to serve as the site for Mussolini’s balcony speeches.

VIEW OF THE WORK IN PROGRESS CIRCA 1900 AERIAL VIEW

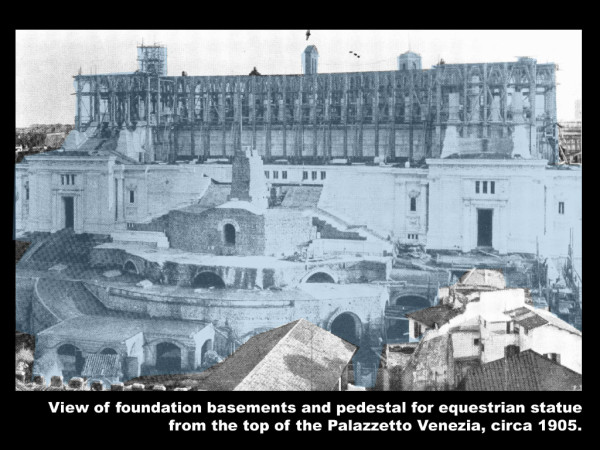

The monument grew incrementally over time, like a work in progress; changing more than once architect’s hands and subject to a succession of works by a constantly updated roster of sculptors and artists. Sacconi continued to modify the design and oversee the construction of the monument until his untimely death in 1905. He was succeeded, after a year hiatus, by a new artistic and technical directorate, headed by Gaetano Koch, Manfredo Manfredi and Pio Piacentini (father of Marcello Piacentini).

SECTION showing the location of the ancient Servian wall, and whose discovery further altered the designs for the monument.

Construction of the base and plinth.

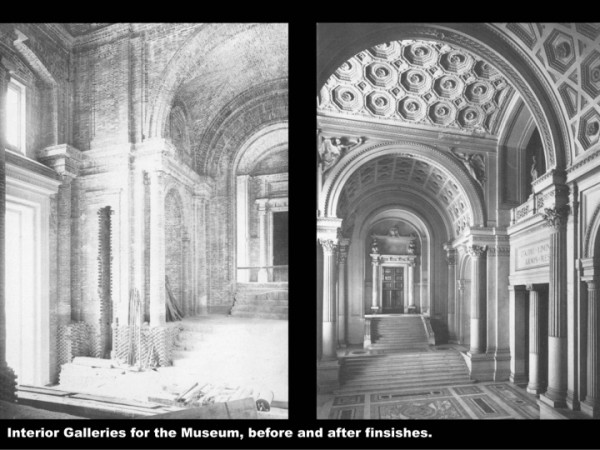

The Design of the monument would be altered to take into account the site context, existing archaeological conditions, the ancient Servian wall, existing aquifers, and other unexpected discoveries. In turn, these transformations to the original project design, in effect reducing the massive fortified appearance and allowing for greater transparency, and better access into and through the monument.

Competitions were held for each of the individual works of art, sculptures, reliefs, fountains, murals.

Crypts, caverns, that came about due to the bulk of the foundations and that would become the serendipitous space for entirely new and unexpected possibilities in programming spaces, like the Risorgimento Museum, archives, and as we will see, the Tomb dedicated to the Unknown Soldier, the Milite Ignoto.

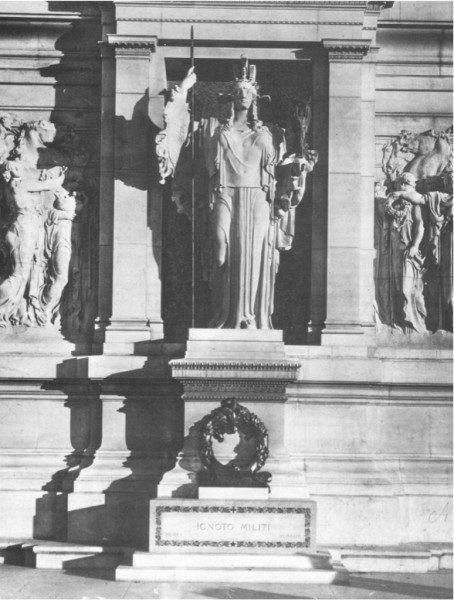

THE CEREMONY OF THE UNKNOWN SOLDIER. The original idea extolling the virtuous sacrifice of a common infantryman, one of thousands disfigured beyond recognition can be attributed to a Colonel Giulio Douhet. Colonel Douhet, embittered with the war’s progress, became an open critic of the Italian Army’s battle tactics in its struggling campaign against Austria. Douhet first proposed that the body of the unknown soldier be placed besides the king’s in the pantheon, though this solution was thoroughly rejected by the royal family. in 1920, after the “Unknown Soldier” was denied the right to burial in the Pantheon, the only logical alternative would become the nation monument to Vittorio Emanuele II.

“AQUILEIA, THE DEAD CITY”

THE GODDESS OF ROME

The very geographical disposition of the ritual, traversing the Italian peninsula from North to South on its way to Rome, served together with the climatic event in the capital to temporarily unify the country’s population. The unfolding sequence of events connecting city to city stimulated a new kind of participatory populism that played surprisingly well to Italy’s growing nationalist sentiment.

MISSING LINK

Until the entombment of the body of the “Unknown Soldier” the Vittoriano lacked a truly populist message. Despite standing smack in the center of the Risorgimento capital, no prior event had succeeded in animating the three-tiered white colossus as did the

commemoration for the unidentified infantryman that took place on November 4, 1921. The ponderous coverage that local papers devoted to the ceremony bears this point out.’ The whole process surrounding the commemoration, from the selection of the body of

an unidentified soldier to the choice of final resting place, was from the very beginning conspicuously placed in the public eye. All the ingredients for a national drama were present: weeping widows and grieving mothers, noted veterans and war heroes, Government, King and Army all took their place on the steps of the monument. The gradual build-up around the event, the public’s participation in the preparative phases, the media attention, the numerous commercial spin-offs, the final show of popular emotion, and even the sporadic protests created a collective sense of drama that seduced for once the whole nation.

According to George Mosse “…at the end of the war, there flourished a new understanding of the fact that a democratic era had been born, an era of mass politics, in which the symbols of the nation had to (if one wanted them to work) attract popular attention and enthusiasm.” “In the end…” Mosse noted, “…all nations made of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier a convenient

central location for the cult of the fallen.16 Such a trend crossed through Italy’s parliamentary culture, penetrating the extreme nationalist groups as well: D’Annunzio’s Fiume legions, and Mussolini’s squadristi were all moving down the same path of mystical exaltation of the war and its human sacrifices. Catholics and socialists were also swept into the event, despite contradictory admonitions coming from their respective leaderships.

The capital’s national destiny was sealed with the almost haphazard placement of the monument to King Vittorio Emanuele II at the end of the city’s central axis at the dead end of the most ancient and sacred of Rome’s archaeological districts. Had this symbol ended up as originally planned adjacent to the modem train station, then it would be rather easy to predict that the city would have continued to develop according to a polycentric pattern of growth. There would not have been the surcharged concentration of ancient and Risorgimento symbolism jammed against the Capitoline Hill. Nor would this monument have mustered the massive popularity it was to eventually engender, were it not for the choice to keep King Emanuele ll’s body in the Pantheon allowing for the “Unknown Soldier” to sweep up the attention.

As long as the Vittoriano remained without the body of the King, the monument remained a sterile architectural symbol in the city’s landscape. But the underclass status of the “Unknown Soldier,” considered undeserving of his due resting place in the Pantheon, was instead given a crypt in the largest and most visible structure being completed in Rome at the time. This historical slippage, where the corporeal presence of the King was exchanged for

one of his subjects, really an unpremeditated act of chance, had a staggering effect on the monument’s future symbolic message.

By the time the rear arterial avenues were completed in the mid thirties— linking Rome to the south and the sea where Mussolini would concentrate the majority of his regional expansion policies in the years to come— the monument came to lord over capital and nation. By extension the piazza before it, became the newest and grandest forum for this modern Italy.

The monument’s slow detachment from this antique fabric, through a steady program of urban demolition, transformed the site into a continuous work in progress. Like Berlin’s Potsdamer Platz in the 1990s, the constant pace of construction concentrated on Piazza

Venezia and its surroundings captivated the public’s ongoing curiosity. The monument stood as a metaphor for the Nation’s early progress in modernization providing a defining and recognisable symbol of Italy’s transformation. The massive monument to Vittorio Emanuele II, despite its exaggerated neo-classical veneer, became a powerful motor for Rome’s urban modernization. With the insertion of the crypt for the “Unknown Soldier” in 1921, the monument would be transformed into a kind of hybrid multi-functional and multi-symbolic architectural container that anticipated future trends in modem architectural design.

In the mean time, the role of the spectator fundamentally changed. The spectator became an engaged participant in the Fascist ritual, no longer a bystander, but an action character in a highly controlled spectacle. There were no more unplanned moments, spontaneous gestures, or comfortable hideaways. The stage for the spectacle was no longer restricted to the fixed proscenium, that remained static as the show unfolded. The fascist spectacle of the mid 1930’s, though a forced public arena, became the dynamic landscape for choreographed movement, crafted to the camera’s eye, orchestrated to radio and sound amplification. But beyond the lock step of the military march, and the athletic precision of gymnastic ballet, the new Italian forum now spread its influence well beyond the confines of piazza Venezia. The modem spectacle, dispersed into many decentralized arenas, including Italy’s growing overseas colonial territories. What remains to be seen, is just how these spaces of orchestrated mass political propaganda spectacles would become supplanted in the years to come with newer rituals, far more spontaneous, yet clearly tied to the spaces of these previous rituals.

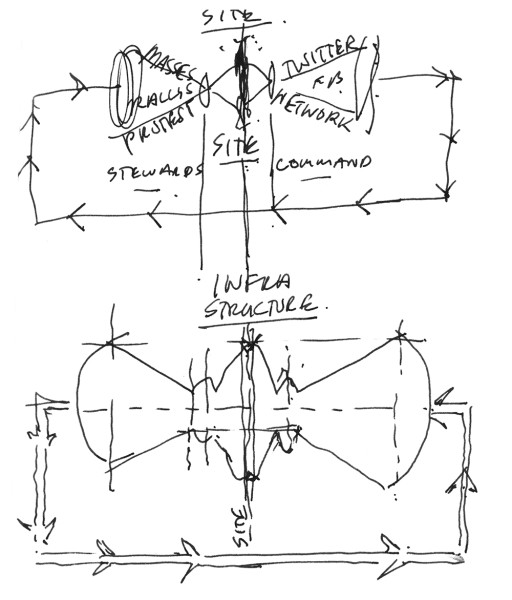

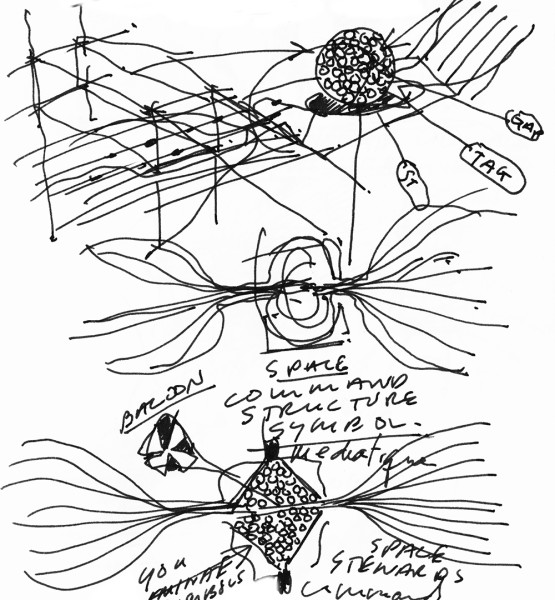

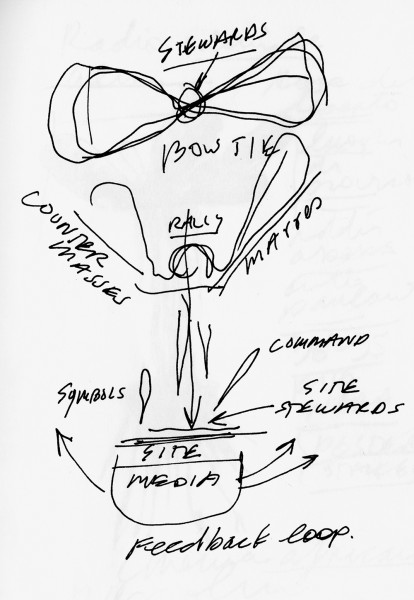

In the following diagrams, I explore the relationship between historical urban spaces, symbolic landmarks, incrementally layered developments, mass rallies, mass protests and spontaneous uses of public space. These diagrams will be further amplified as I expand this study into a growing number of areas of public space and the built environment.